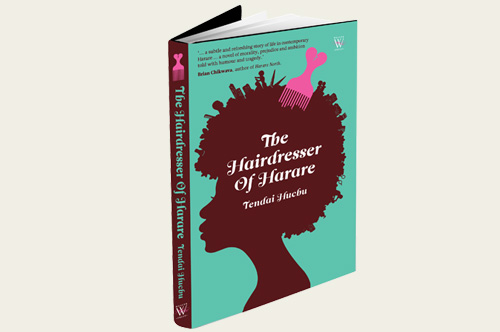

A Q&A with Zimbabwean author, Tendai Huchu

What inspires your writing?

Day to day life, the ordinary and mundane, flashes of imagination in which lies the possibility to peer behind the veil. People. Cities. Other writers.

Have you always been a writer? How did it all begin?

It’s almost impossible to pinpoint the exact point at which I became a writer. Was it my apprenticeship in my high school newspaper, could it have been a proto manuscript written when I was sixteen, perhaps it was when I first read Dostoevsky in my early 20s and decided to have a go. The true answer probably lies in a constellation that joins all these dots.

Have you found it limiting living abroad but writing about Zimbabwe?

No.

Which local or international novelist do you recommend to read right now?

NoViolet Bulawayo, the author of We Need New Names.

What are you currently working on?

A new manuscript called The Maestro, The Magistrate, & The Mathematician.

Your brief thoughts on Zimbabwe’s contemporary literary scene – alive and well or “alive but dead”?

We have a few good writers I can point to, Bryony Rheam, Petina Gappah, Irene Sabatini, Brian Chikwava. You’ll notice most of the people on this list are female. If you look at Zimbabwean literature today, and thinking of other writers still in the shadows but emerging, Novuyo Tshuma, Barbara Mhangami, Melissa Tandiwe Myambo, etc, it becomes even more evident that male writers such as myself are at the periphery while the female writers occupy centre stage, and this is through pure merit alone.

When you aren’t reading or writing, what are you doing?

Dealing with real life, paying bills, stressing about one thing or the other, worrying the world is coming to an end, you know – the usual stuff.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Being dropped by my publisher, which showed me the weaknesses in my own work, but more importantly helped me to realise that self-belief was important, and ultimately, for all the romantic myths we spin about writing, it is just business.

What is your favourite journey?

Wtf?

Would you call the Hairdresser of Harare political in any way?

It is political in the sense that everyday human life is lived within politically defined parameters. Where you may or may not go, who you may or may not marry, what you may or may not smoke, the things you can or cannot say – all these things are embedded within a political framework. The Hairdresser of Harare is political only in the sense that all literature is political.

Got any personal anecdotes from visits to your barber!

I wear dreadlocks, in case you haven’t noticed. A visit to the barber is quite out of the question! (whoops … interviewer)

What do you miss most about home?

The people.

Sadza, rice and chicken or “fast food”?

You can never go wrong with sadza.